The Salk Institute for Biological Studies, located in La Jolla, California, was commissioned by Jonas Salk, developer of the first safe and effective polio vaccine in 1960. Salk, who envisioned the Institute to contribute to humankind’s betterment, selected the renowned architect Louis I. Kahn to design the research facility. Salk’s vision for the Institute required Kahn to design spacious and flexible laboratory spaces adapted to the ever-changing needs of science, using simple, strong, durable, and low-maintenance materials. Today, the original buildings of the Salk Institute are recognized as historical landmarks, having been designated as such in 1991.

The Salk Institute Technical Information

- Architects: Louis Kahn | Biography & Bibliography

- Location: 10010 N Torrey Pines Rd, La Jolla, California, United States

- Structural engineer: August Komendant

- Structural system: Vierendeel trusses

- Topics: Modernism, Primitive Shapes, Voids, Concrete

- Project Year: 1959 – 1965

- Photographs: © ArchEyes, © Thomas Nemeskeri

Hope lies in dreams, in imagination and in the courage of those who dare to make dreams into reality.

– Jonas Salk

The Salk Institute Architecture Photographs

The Design Process

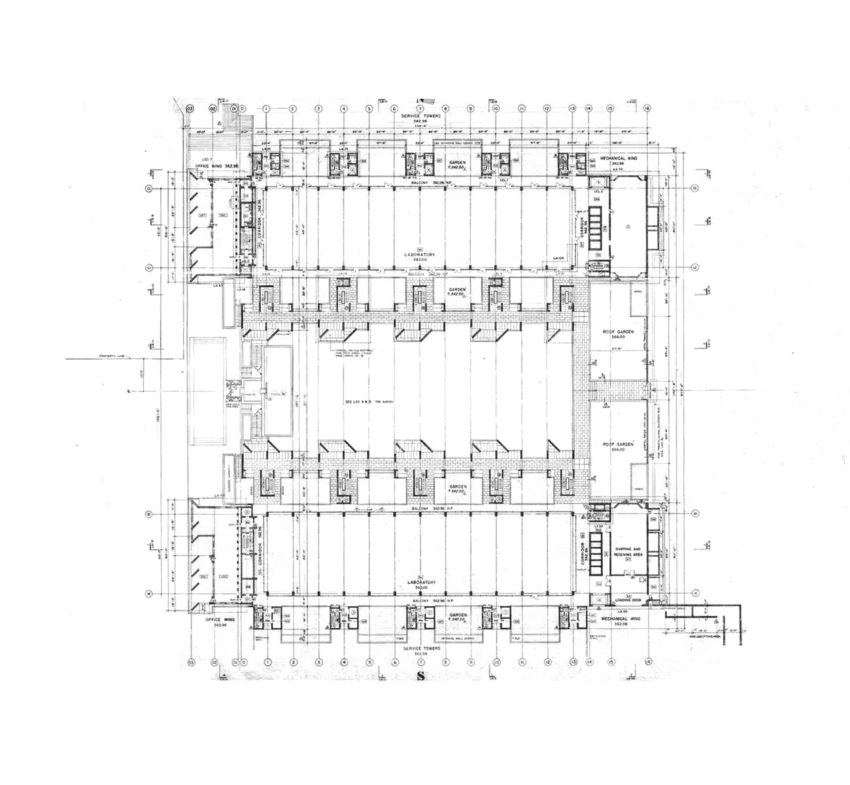

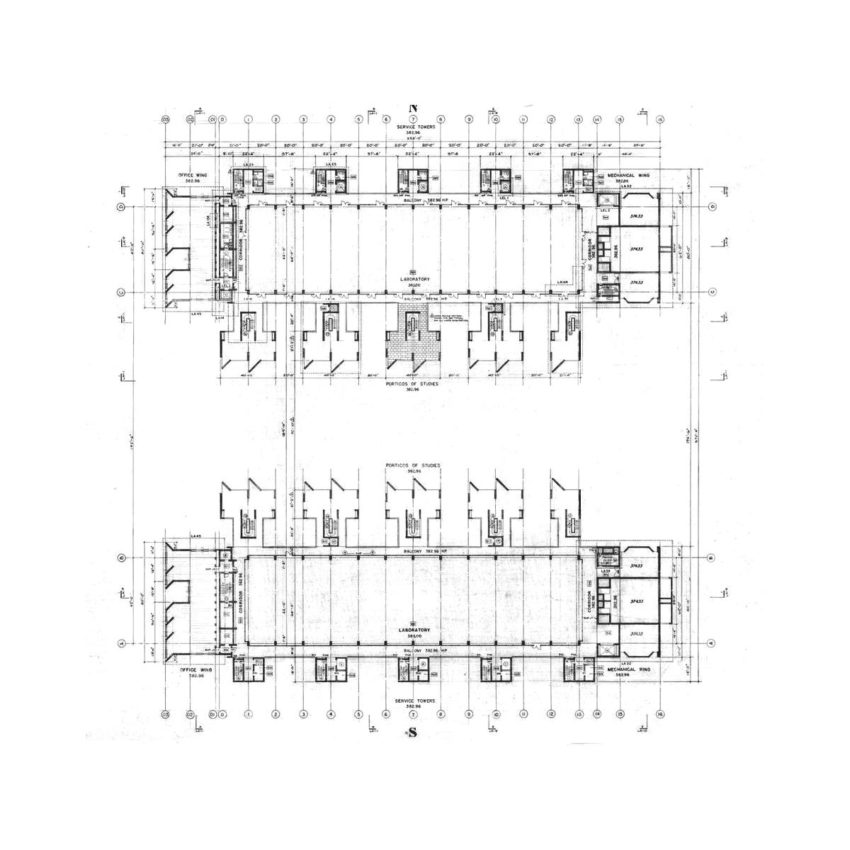

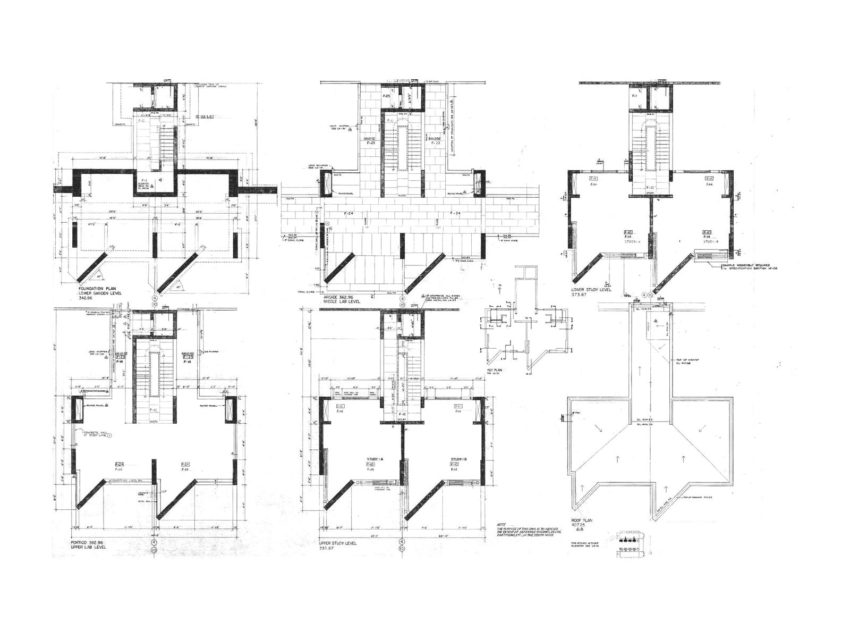

Kahn’s masterwork consists of two mirror-image structures – each six stories tall – that flank a grand travertine courtyard. Three floors house laboratories and the three levels above them provide access to utilities. Towers jutting into the courtyard provide study space for senior faculty. The towers at the east end contain heating, ventilating, and other support systems. At the west end are six floors of offices overlooking the Pacific Ocean. A total of 29 structures join to form the Institute.

In the complex’s basement, there are different colored water walls because Kahn was experimenting with the mixtures. The buildings themselves have been designed to promote collaboration; thus, there are no walls separating laboratories on any of the floors. The lighting fixtures on the roof slide along rails, thus reflecting the collaborative and open philosophy of the Salk Institute’s science.

The impact of Kahn’s architecture can be particularly felt in the travertine courtyard. Important to note are Kahn’s imaginative use of space and high regard for natural light. In response to Salk’s request that the Institute be a welcoming, inspiring environment for scientific research, Kahn flooded the laboratories with daylight.

He built all the exterior walls out of large, double-strength glass panels to create an open, airy work setting on the laboratory levels. Local zoning codes restricted the buildings’ height so that the first two stories had to be underground. However, this did not prevent the architect from bringing in daylight: he designed a series of light wells 40 feet long and 25 feet wide on both sides of each building to bring daylight into the lowest level.

Salk and Kahn’s collaboration resulted in a blueprint uniquely suited to a scientific research center. The next challenge was realizing it using materials that could last for generations with minimal maintenance. Chosen to meet these criteria were concrete, teak, lead, glass, and steel. The poured-in-place concrete walls deliver the first bold impression for visitors. Kahn returned to Roman times to rediscover the waterproof qualities and the warm, pinkish glow of “pozzolanic” concrete. Once the concrete was set, he allowed no further processing of the finish—no grinding, no filling, and above all, no painting. The architect also chose an unfinished look for the teak surrounding the study towers and west office windows and instructed that no sealer or stain be applied to the teak. The building’s exterior, with only minor, required maintenance; today looks much as it did in the 1960s.

The open courtyard of travertine marble acting as a facade to the sky adds to the building its monumental nature. In 1992, the Salk Institute received a 25-Year Award from the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and was featured in the AIA exhibit Structures of Our Time: 31 Buildings That Changed Modern Life. The Salk Institute has been described in the San Diego Union-Tribune as the single most significant architectural site in San Diego.

Architecture Design Anecdote

After two years of design work, and after the design had been approved and meetings with building contractors had begun, Kahn and the Salk Institute abruptly decided to reduce the number of laboratory buildings from four narrow ones to two wider ones and to increase the number of floors per building from two to three. Komendant re-engineered the structure and produced a new set of drawings with a speed that professor Leslie described as “legendary.” Komendant also trained the construction workers in techniques for creating a highly refined concrete finish.

The Plaza of the Salk Institute

The construction started with Kahn still intending to put a garden court between the two blocks. However, as work continued, Kahn realized that he did not know what form it should take. Kahn had seen Barragán’s work in an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, and subsequently, Kahn met Barragán in Mexico City in 1965 and invited him to review the design of the court.

For well over a year, I made studies of the kind of trees and their placement in the garden. I could not decide, partly because of the diversity of advice regarding what flora would survive the exposure and winds of the Pacific. I called Luis Barragán of Mexico. I had met him several months before. I saw his house, and I sensed his incomparable sensitivity to Nature. I asked Barragán to help select the trees of Garden. He came readily.

– Louis Kahn

Barragán visited the site with Louis Kahn and Jonas Salk in February 1966, returning in May. The current proposals for the court were shown to Barragan. The plans suggested planting nine Australian tea trees to line each side of the rill, and two rows of red birch trees sited perpendicular to the rill that would serve to contain each end of the court spatially—the birches at the west filling the dry pools, and the others immediately to the east of the roof garden. The ground surface was to be lawn, retaining the paving around the perimeter, and subdivided by the rill and drainage channels.1

To Kahn’s surprise, Barragán told Kahn that he should “. . . not add one leaf, nor plant, not one flower, nor dirt. Instead, make it a plaza with a single water feature. [. . .] If you make a plaza, you will have another facade to the sky.’ Kahn was so jealous of this idea that he could not help adding to it, saying, ‘then we would get all those mosaics for nothing,’ pointing to the Pacific Ocean.2

To Kahn, Barragán’s advice was a breakthrough, and MacAllister noted that Kahn “. . . was thinking of the open space as a ‘garden’ from the start, and he couldn’t get past that because of the word. When Barragán

said ‘plaza,’ Lou was free to make the change.” 3

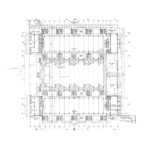

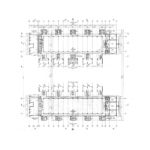

The Salk Institute Architecture Plans

The Salk Institute Architecture Gallery

About Louis Kahn

Louis Kahn (1901 – 1974) was a renowned American architect who left a lasting impact on 20th-century architecture. Based in Philadelphia, Kahn’s works were characterized by their monumental and monolithic style, which emphasized the weight, materials, and construction of buildings. Through his innovative proposals and teachings, Kahn rose to become one of the most influential architects of the 20th century.

Full Bio of Louis Kahn | Works of Louis Kahn

- Louis I. Kahn Collection, University of Pennsylvania, 030.I.C.540.29_LSDL-1, revised 8 Oct 1965.

- Kahn to James Britton, 12 June 1973, Louis I. Kahn Collection, University of Pennsylvania,

0030.II.A.27.31. - Louis Kahn: Essential Texts by