Completed in 1955 by the Franco-Swiss architect Le Corbusier, the Ronchamp Chapel or “Notre Dame du Haut” is one of the most radical designs of Le Corbusier’s late style. Located on the top of a hill above the village of Ronchamp, it is the latest of a long history of pilgrimage chapels erected on the site. The previous structure dated from the 4th century and was destroyed during the Second World War. The thick, curved walls – especially the buttress-shaped south wall – and the vast shell of the concrete roof give the building a massive, sculptural form.

Le Corbusier’s Ronchamp Chapel Technical Information

- Architects: Le Corbusier | Bio of Le Corbusier

- Location: Colline de Bourlémont, 70250 Ronchamp, Haute-Saône, France

- Topics: UNESCO, Chapels, Brutalism. Modernism, Concrete

- Site Area: 2.734 ha

- Project Year: 1950-1955

- Photographs: © Cemal Emden, © Atelier Le Corbusier and Flickr Users: © Wojtek Gurak, © Trevor Patt, © Steve Silverman

Here we will build a monument dedicated to nature and we will make it our lives’ purpose.

– Le Corbusier, 1950

Le Corbusier’s Ronchamp Chapel Photographs

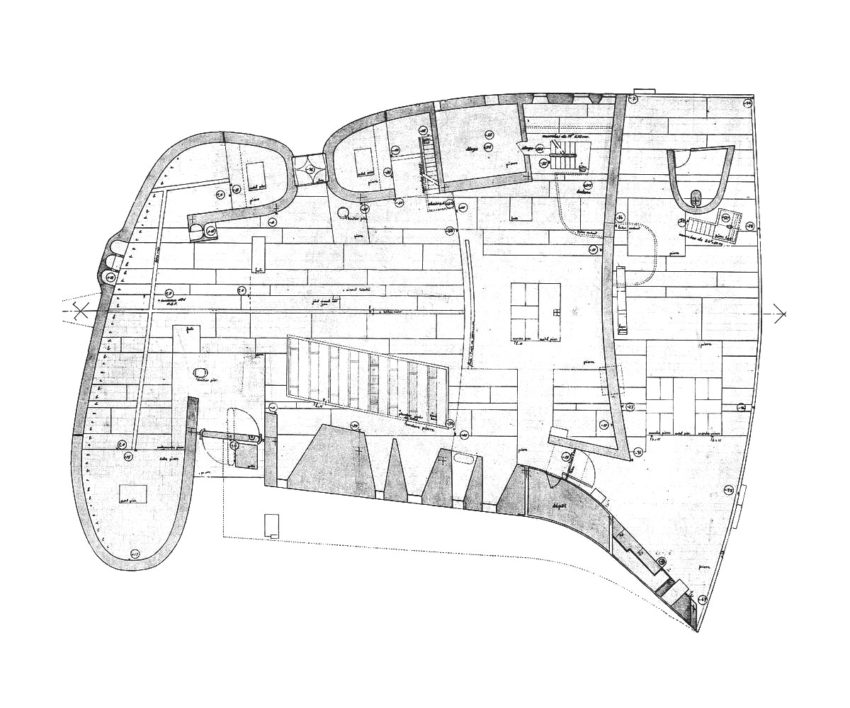

Commissioned by the Association de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame du Haut, the chapel is a simple design with two entrances, the main altar, and three chapels beneath towers. After the war, it was decided to rebuild the chapel on the same site. Warning against the decadence of the institution, reformers within the Church looked to renew its spirit by embracing modern art and architecture as representative concepts. Father Marie-Alain Couturier, who would also sponsor Le Corbusier for the La Tourette, engaged the architect.

The chapel at Ronchamp is singular in Le Corbusier’s oeuvre. It departs from his standardization and machine aesthetic principles, giving in instead to a site-specific response. Le Corbusier’s mentioned it was the site that provided an irresistible genius loci, with the horizon visible on all four sides of the hill and its historical legacy for centuries as a place of worship.

This historical legacy was woven in different layers into the terrain – from the Romans and sun-worshippers before them to a cult of the Virgin in the Middle Ages, right through to the modern church and the fight against the German occupation. Le Corbusier also sensed a sacred relationship with its surroundings – the Jura mountains in the distance and the hill itself, dominating the landscape.

The nature of the site would result in an architectural ensemble that has many similarities with the Acropolis – starting from the ascent at the bottom of the hill to architectural and landscape events along the way, before finally terminating at the Sanctus Sanctorum itself – the chapel. You cannot see the building until you reach nearly the crest of the hill. From the top, magnificent vistas spread out in all directions.

Ronchamp Construction and Structure

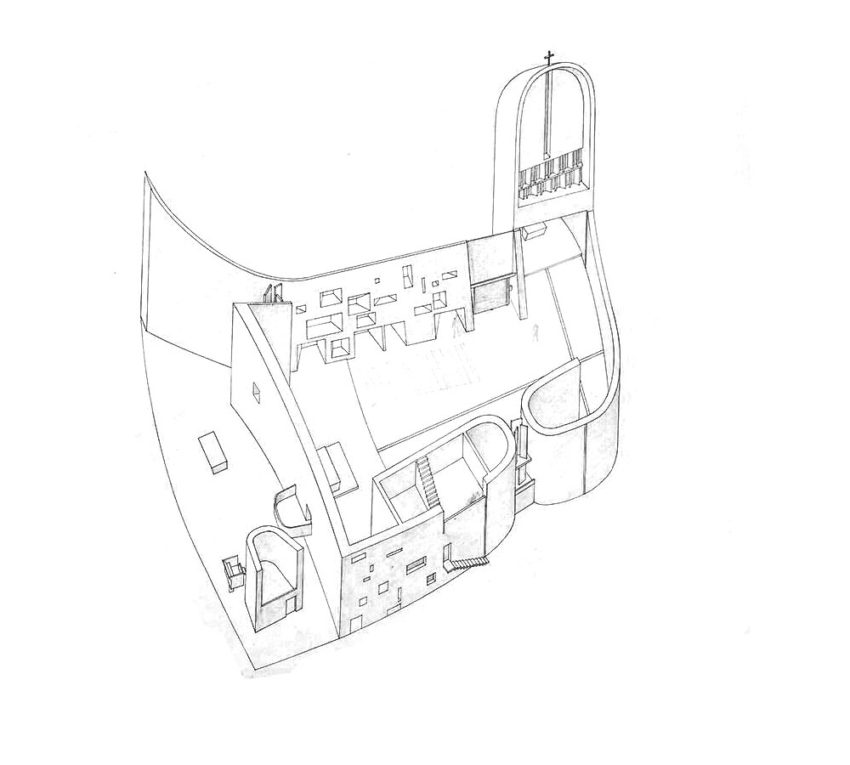

The shell has been put on walls which are absurdly but practically thick. Inside them however are reinforced concrete columns. The shell will rest on these columns but it will not touch the wall. A horizontal crack of light 10cm wide will amaze.

– Le Corbusier1

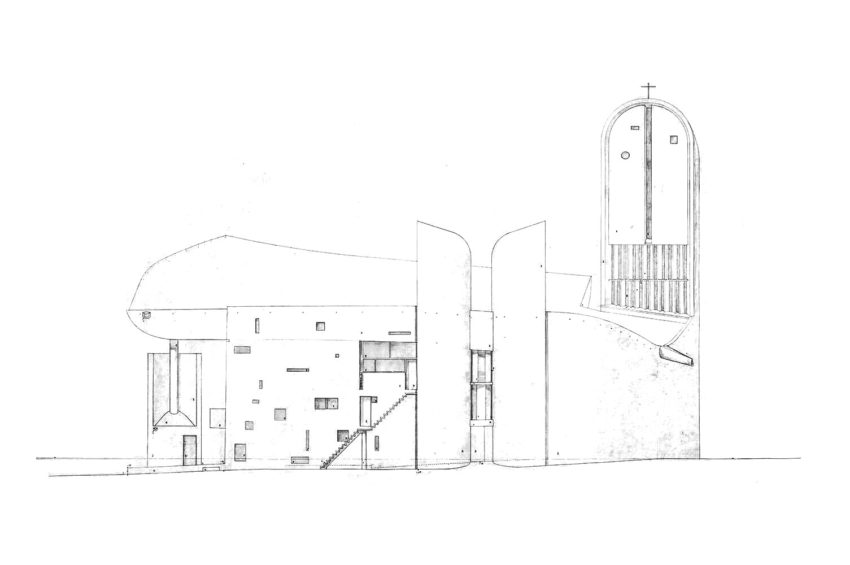

The structure is mainly made of concrete and is comparatively small, enclosed by thick walls. The upturned roof is supported on columns embedded within the walls, like a sail billowing in the windy currents on the hilltop. In the interior, the spaces left between the walls and roof are filled with clerestory windows. The asymmetric light from the wall openings further reinforces the sacred nature of the space and enhances the relationship of the building with its surroundings. The lighting in the interior is soft and indirect, from the clerestory windows and reflecting off the whitewashed walls of the chapels with projecting towers.

The main part of the structure consists of two concrete membranes separated by a space of 6’11”, forming a shell that constitutes the roof of the building. This roof, both insulating and watertight, is supported by short struts, which form part of a vertical surface of concrete covered with “gunite” and which, in addition, brace the walls of old Vosges stone provided by the former chapel which was destroyed by the bombings.

These walls, which are without buttresses, follow in plan the curvilinear forms calculated to provide stability to this rough masonry. A space of several centimeters between the shell of the roof and the vertical envelope of the walls furnishes a significant entry for daylight. The floor of the chapel follows the natural slope of the hill down towards the altar. Certain parts, in particular those upon which the interior and exterior altars rest, are of beautiful white stone from Bourgogne, as are the altars themselves. The towers are constructed of stone masonry and are capped by cement domes. The vertical elements of the chapel are surfaced with mortar sprayed on with a cement gun and then white-washed — both on the interior and exterior.

The concrete shell of the roof is left rough, just as it comes from the formwork. A built-up roofing achieves water tightness with an exterior cladding of aluminum. The interior walls are white; the ceiling grey; the bench of African wood created by Savina; the communion bench is of cast iron made by the foundries of the Lure.

Ronchamp South Wall

[The] south wall provokes astonishment. Vertical triangular frames of reinforced concrete 16 cm thick varying, at the base, from a width of 3,70 m to 1,40 m to 50 cm at the top, carrying the immense, spreading shell of the roof; the rest, the bays, embrasures and splays which break up the interior wall (and scarcely puncture the facade) is a membrane of concrete 4 cm thick sprayed on to expanded metal by cement gun.

– Le Corbusier1

The South wall of Ronchamp is a creature of its own. Le Corbusier spent months trying to perfect the outside wall rather than designing a straight, 50 cm thick concrete piece. He came up with a wall that starts as a point on the east end and expands to up to 10 feet wide on its west side. As it moves from east to west, it curves towards the south. To further develop his design’s complexity, Le Corbusier decided to make the wall’s windows extraordinary.

The openings slant towards their centers at varying degrees, letting in light at different angles. The different-sized windows are scattered in an irregular pattern across the wall. Le Corbusier reportedly insisted that the shapes and patterns were not arbitrary but derived from a proportional system based on the Golden Section. Furthermore, the glass that closes the windows off is set at alternating depths. This glass is sometimes clear but is often decorated with small stained glass pieces in red, green, and yellow colors. These stained pieces radiate like rubies, emeralds, and amethysts and act as the jewels of the already complex wall. After this extensive design, Le Corbusier decided not to make the southern partition a bearing wall. Instead, the building’s roof is supported by concrete columns that make it appear to float above the rest of the space. The effect produced allows a strip of light to enter the building, thus lighting the space further and making the church feel more open.

In a final move of symbolism, Le Corbusier filled the inside of the wall with the rubble from the previous chapel that stood at the location. Thus the old church, and all of its history, would remain on the site.

This billowing concrete roof was planned to slope toward the back, where a fountain of abstract forms is placed on the ground. When it rains, the water comes pouring off the roof and down onto the raised, slanted concrete structures, creating a dramatic natural fountain.

Near the chapel, Le Corbusier built two low buildings, the caretaker’s house and the pilgrims’ house consisting of a restaurant and two dormitories. The site is completed by a step pyramid dedicated to the victims of the second world war.

Le Corbusier´s Ronchamp Chapel Plans

Le Corbusier Ronchamp Chapel Image Gallery

About Le Corbusier

Le Corbusier, or Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (1887 -1965), was an internationally influential Swiss architect and city planner whose designs combined the functionalism of the modern movement with bold, sculptural expressionism. He belonged to the first generation of the International School of Architecture.

In his architecture, he joined the functionalist aspirations of his generation with a strong sense of expressionism. He was the first architect to make a studied use of rough-cast concrete, satisfying his taste for asceticism and sculptural forms. In 2016, 17 of his architectural works were named World Heritage sites by UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization).

Le Corbusier’s most celebrated buildings include the Villa Savoye outside Paris, Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp and the Unité d’Habitation in Marseille. He is also known for his work in urban planning, which included the design of Chandigarh, India, in the 1950s.

Full Bio of Le Corbusier | Other works from Le Corbusier

- Source: Le Corbusier: the Chapel at Ronchamp by

- Source: Precisions: On the Present State of Architecture and City Planning by Le Corbusier, 1930.