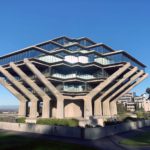

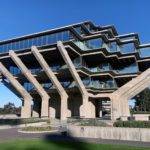

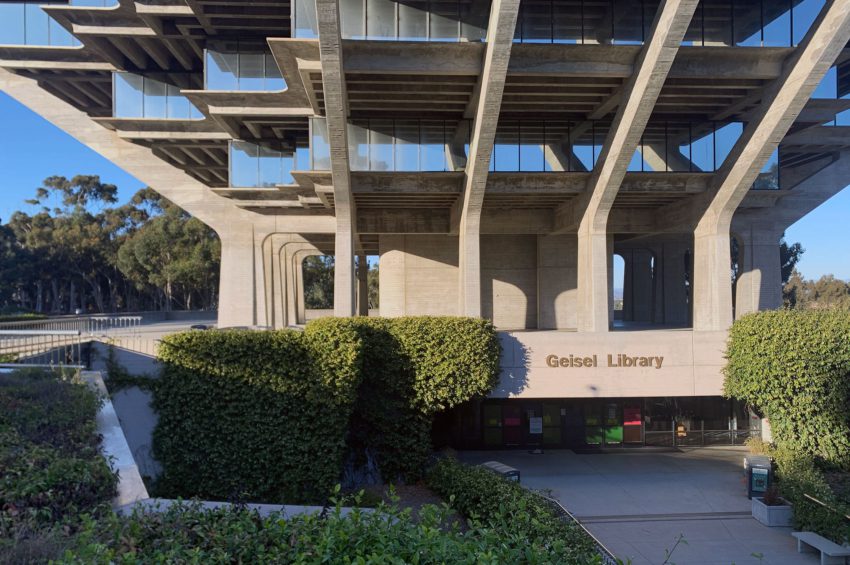

The Geisel Library, designed in the 1960s by architect William Leonard Pereira, is renowned for its futuristic design, reminiscent of the space age. Pereira, also known for projects like the Transamerica Pyramid in San Francisco, has given the library a distinctive architectural style that blends elements of brutalism and futurism. This has made the Geisel Library one of the most recognizable buildings in San Diego.

The Geisel Library Technical Information

- Architects1-4: William L. Pereira & Associates

- Location: University of California San Diego, 9500 Gilman Dr, La Jolla, CA 92093, United States

- Client: University of California San Diego

- Topics: Brutalism, Concrete, Libraries, Pyramids

- Area: 16.350,93 m2

- Cost: $ 5.4 million

- Project Year: 1968-1970

- Photographs: © ArchEyes, © Maciek Lulko

If I Bowdlerize adjectives to describe the proposed new library at San Diego I presume that golldarndest would describe the building that Pereira came up with to satisfy the programmed requirements. […] Obviously architects recently have been ivorried about stodginess of libraries, and have done violence to library needs in some of California’s efforts to overconie this stodginess. Pereira has dramatically done the aesthetic task within the scope of library needs. I wish I could talk with my hands on paper to describe the ‘sculptural, tour de force’ building being considered at San Diego.

– Donald C. Davidson 5

The Geisel Library Photographs

History of the Geisel Library

The Geisel Library is named in honor of Audrey and Theodor Seuss Geisel (better known as Dr. Seuss) for their generous contributions to the library and their devotion to improving literacy. The Geisel’s were long-time residents of La Jolla, where UC San Diego is located.

The distinctive original building was designed in the late 1960s by William Pereira to sit at the canyon’s head. Built as part of the University of San Diego’s library system, the building has been described as hands holding a stack of books. The building gets its brutalist label from the raw concrete piers that support the building, angle, and extent outwards. The design is full of energy as the changing façade varies from level to level and side to side. William Pereira & Associates prepared a detailed report in 1969. Pereira originally conceived a steel-framed building, but this was changed to reinforced concrete to save on construction and maintenance costs. This change of material presented an opportunity for a more sculptural design.

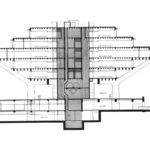

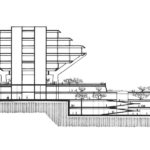

Design of the library

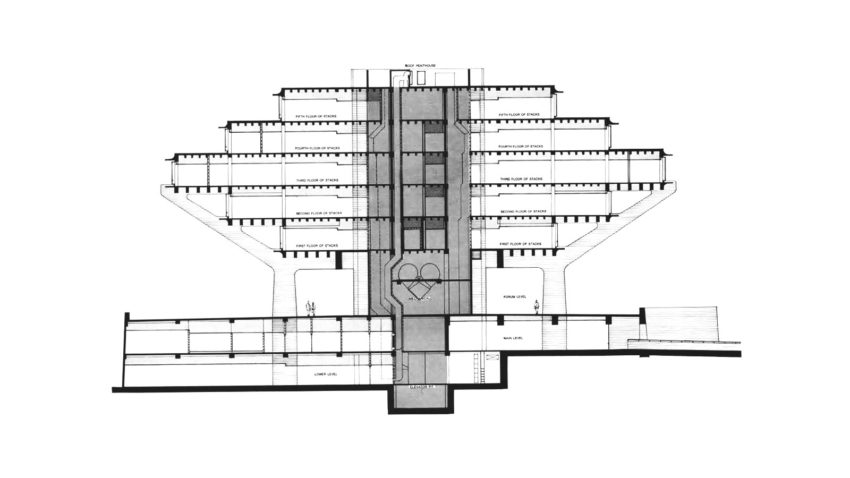

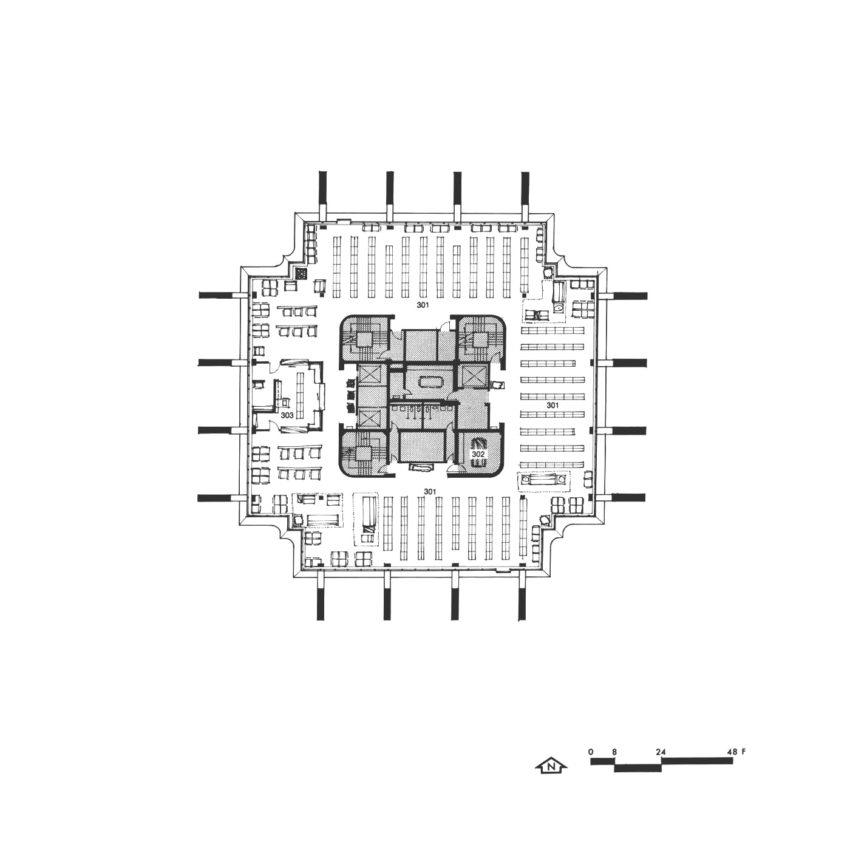

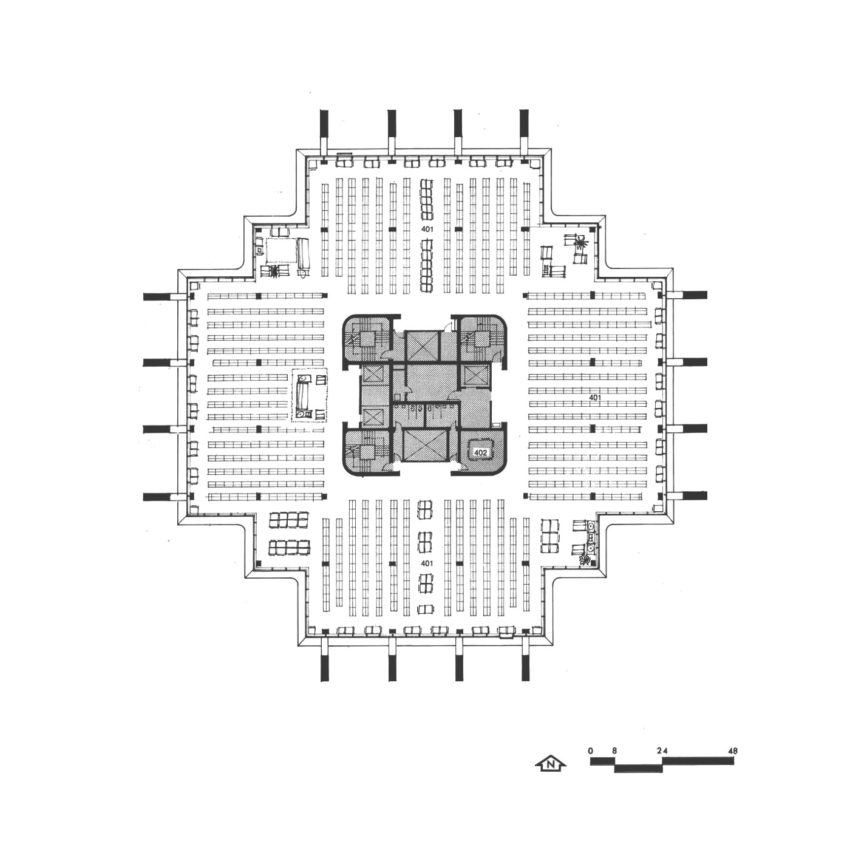

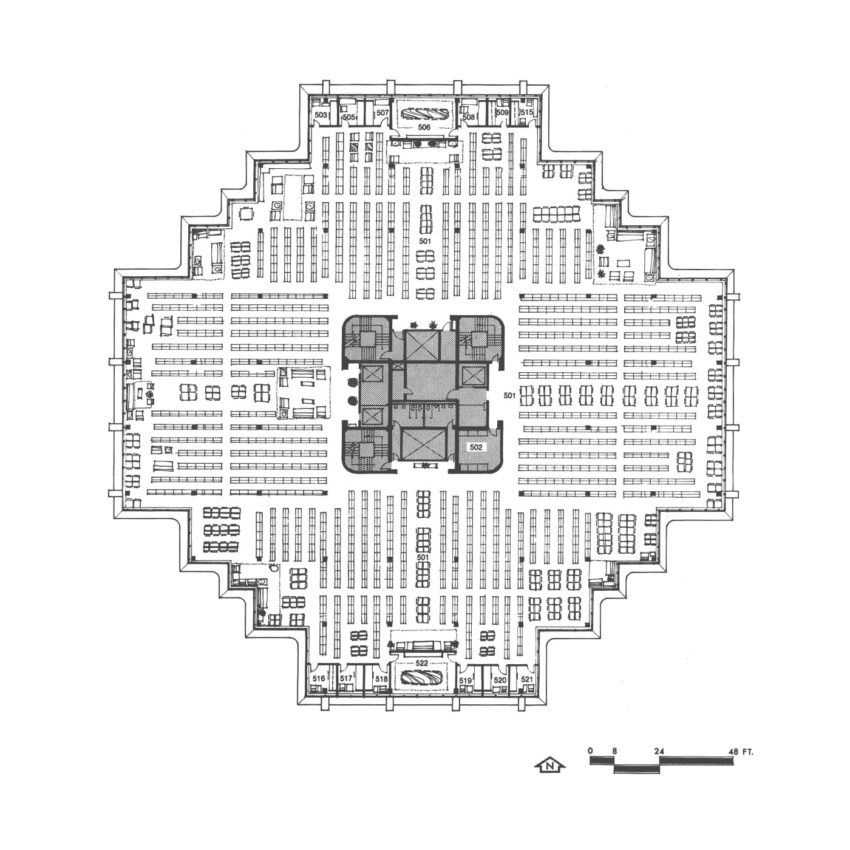

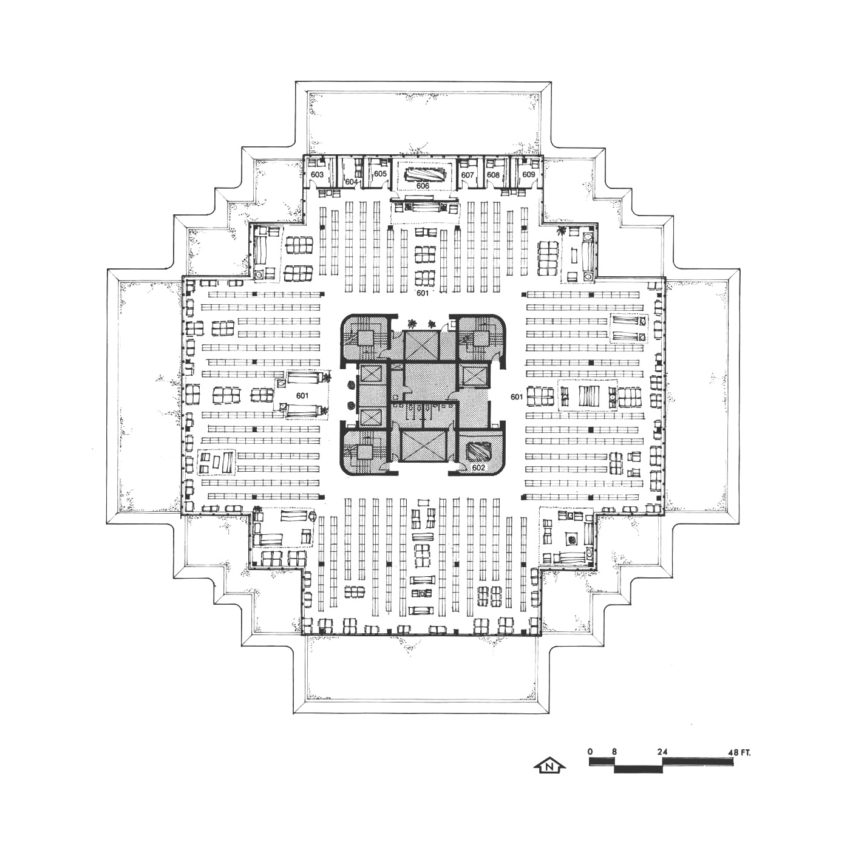

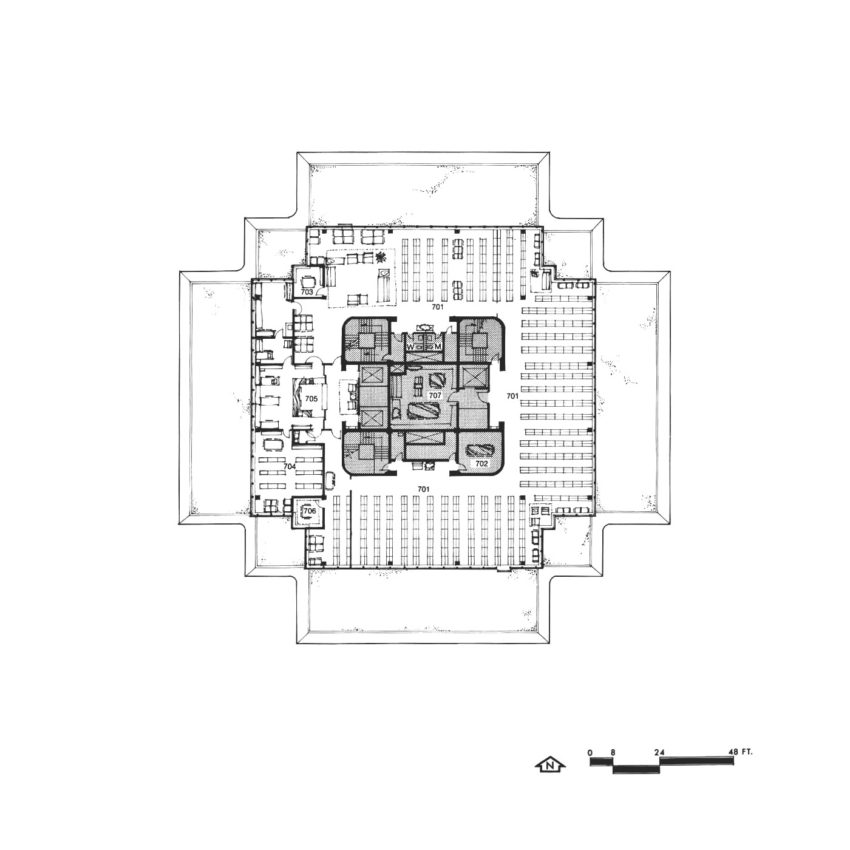

It was envisioned that future additions to the original building would form terraced levels around the tower base descending into the canyon. In keeping with the original master plan, these are deliberately designed to be subordinated to the existing library’s strong, geometrical form. Within its two subterranean levels are the other library sections as well as study spaces and computer labs. Its tower rises 8 stories to a height of 110 ft (33.5 m)—the five upper stories of the tower house collections, individual study space, and group study rooms.

One unusual feature of the library is that the lower levels are numbered 1 and 2, and the upper floors are numbered 4 to 8. That has given rise to several fanciful explanations for why the third floor is apparently sealed off and not accessible from elevators or steps.

One of the more popular stories is that the building’s design had not considered the eventual weight of books in the library. Hence, the third floor has been left empty, a common urban legend associated at different times with many other university libraries.

In reality, the “missing” third floor is actually the open/outside forum. There is no other third floor, blocked off or otherwise. It is made of reinforced concrete, and an emergency exit helps students from the 4-8 floors get out without going to the second floor. The “third floor” is actually two separate levels. The third-floor landings in the public stairwells open to the concrete platform outside the library, originally intended to be used for sculpture displays, acoustic music, impromptu outdoor conversations, an open public meeting area, and poetry readings.

Snake Path

The Geisel forum’s east side is literally and symbolically connected to Warren Mall by the Stuart Collection work Snake Path, Alexis Smith’s 560-foot-long slate tile path that winds towards the library. Its route passes a giant granite Paradise Lost and a small garden of fruit trees.

The Geisel Library Plans

The Geisel Library Image Gallery

About William L. Pereira

William Leonard Pereira (1909 – 1985) was an American architect from Chicago, Illinois, noted for his futuristic designs of landmark buildings such as the Transamerica Pyramid in San Francisco. Remarkably prolific, he worked out of Los Angeles and was known for his love of science fiction and expensive cars but mostly for his unmistakable architectural style, which helped define mid-20th century America’s look. His material of choice in creating his unique geometric forms was pre-cast concrete. Working in this medium, he could create his impressive facades by simply attaching them as panels onto the building’s steel frame.

- Technical Architect: Robert A. Thorburn

- Structural Engineer: Brandow & Johnston

- Electrical Engineer: Frumhoff & Cohen

- Construction Company: Neilsen Construction Co

- Extract from the original report of the building published by William Pereira & Associates. Quote by Donald C. Davidson, a University Librarian at the University of California at Santa Barbara

My sister saved this internet site for me and I have been going through it for the past several hrs. This is really going to assist me and my classmates for our class project. By the way, I like the way you write.