The Florence Cathedral, officially known as the Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore, stands as an iconic symbol of Florence, Italy. The cathedral’s construction commenced in 1296, following Arnolfo di Cambio’s Gothic design. By 1436, the cathedral’s structural completion was achieved, featuring Filippo Brunelleschi’s masterful engineering of the distinctive dome. Adorning the basilica’s exterior are polychrome marble panels in varying hues of green and pink, framed by white borders. A detailed 19th-century Gothic Revival facade, crafted by Emilio De Fabris, further enhances the cathedral’s remarkable presence.

Florence Cathedral Technical Information

- Architects: Filippo Brunelleschi + Arnolfo Di Cambio + Emilio de Fabris

- Location: Florence, Tuscany, Italy

- Topics: Unesco World Heritage, Gothic Style, Romanesque, Renaissance, Marble

- Area: 8,300 m2 (89,000 sq ft)

- Height2-4: 114.5 m (376 ft)

- Project Year: 1296 – 1436

- Photographs: Sources: Unsplash & Flickr

Do not share your inventions with many; share them only with the few who understand and love the sciences.

– Filippo Brunelleschi1

Florence Cathedral Photographs

Brunelleschi’s Enigmatic Dome: Santa Maria del Fiore

Almost 600 years ago, after it was built, Filippo Brunelleschi’s dome of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, Italy, remains the largest masonry dome ever built. Leaving no plans or sketches behind, some of the secrets of its construction that Brunelleschi pioneered are still an enigma today.

In 1418 the town fathers of Florence finally addressed a monumental problem they’d been ignoring for decades: the enormous hole in the roof of their Cathedral. Filippo Brunelleschi was tasked with building the largest dome ever seen at the time. He had no formal architecture training. Yet experts still don’t fully understand the brilliant methods he used in constructing the dome, which tops the Santa Maria del Fiore cathedral in Florence, Italy.

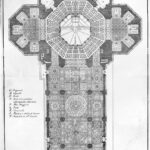

The cathedral complex in Piazza del Duomo includes the Baptistery and Giotto’s Campanile. These three buildings are part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site covering the historic center of Florence and are a major tourist attraction of Tuscany. The basilica is one of Italy’s largest churches, and until the development of new structural materials in the modern era, the dome was the largest in the world. It remains the largest brick dome ever constructed.

History of the Florence Duomo

The Florence Duomo, also known as Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral, is located in Duomo Square. Its construction began at the end of the 13th century under the design of Arnolfo di Cambio, a famous architect and sculptor who loved the Gothic style.

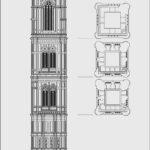

The Cathedral has a central nave and two side aisles plus a rear apse. When di Cambio passed away, the Cathedral’s construction was postponed and resumed in 1334 by Giotto, who designed the bell tower. However, the construction was interrupted again in 1337 after his death. The construction of this magnificent project continued with Andrea Pisano and Francesco Talenti finalizing its construction in 1359. Giotto’s Campanile is 85 m high and it is possible to climb to the top through its 414 steps, from where it is possible to appreciate a fantastic view of Florence.

In the mid of the 14th century, Florentine artists put aside the Gothic style and incorporated the Roman style. The Gothic air of the Cathedral was hidden behind the red marble of Siena, the white of Carrara, and the green of Prato. The metalsmith Lorenzo Ghiberti and the sculptor Filippo Brunelleschi had the privilege of finishing the Cathedral of Florence

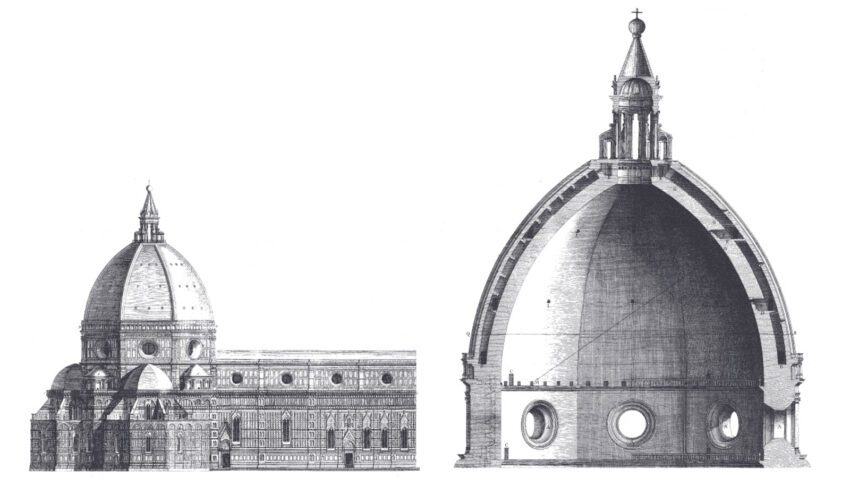

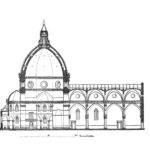

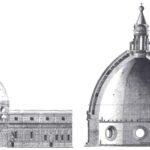

Brunelleschi sculpted the statues for the dome and designed an innovative project to make the Florentine Cathedral the largest of its time. Brunelleschi started with the project’s construction by 1421; the polygonal base had already been completed, while the dome was completed 15 years later. The red dome of the Cathedral was then the largest in the world, 45 m in diameter and 100 m high and soon became the symbol of Florence.

The facade of the Cathedral was destroyed at the end of the 16th century, and Emilio de Fabris redesigned it, made some modifications, and incorporated marble in different colors.

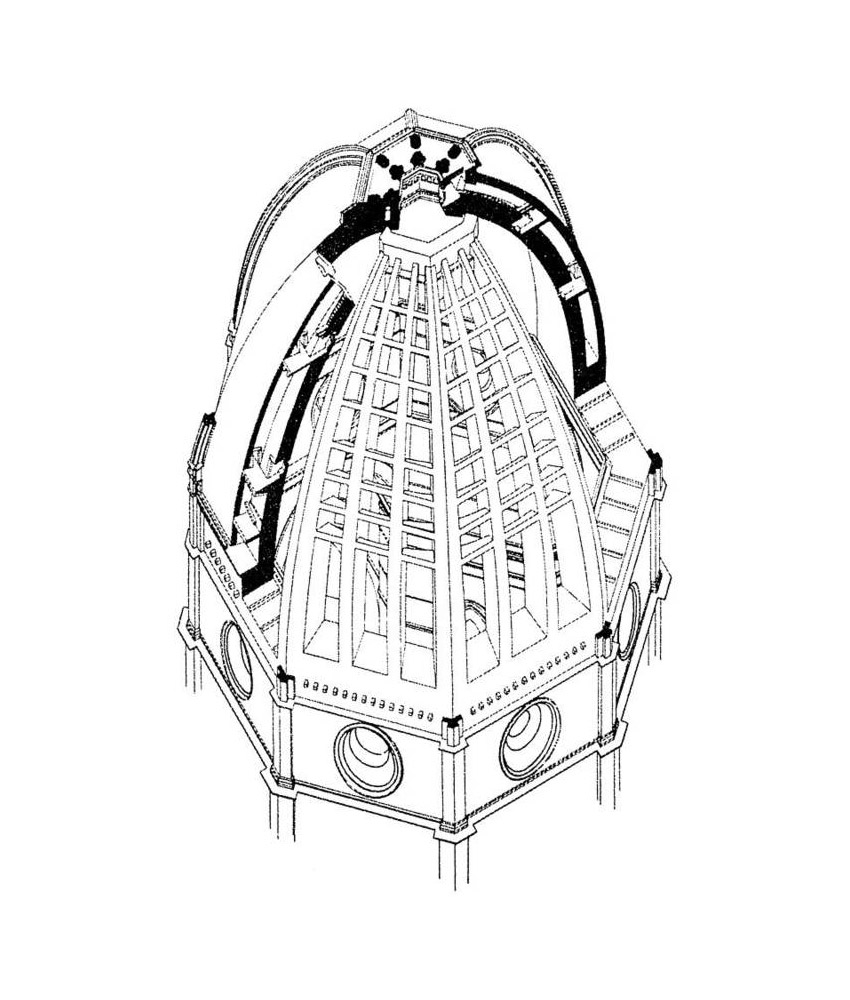

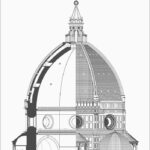

Florence Dome

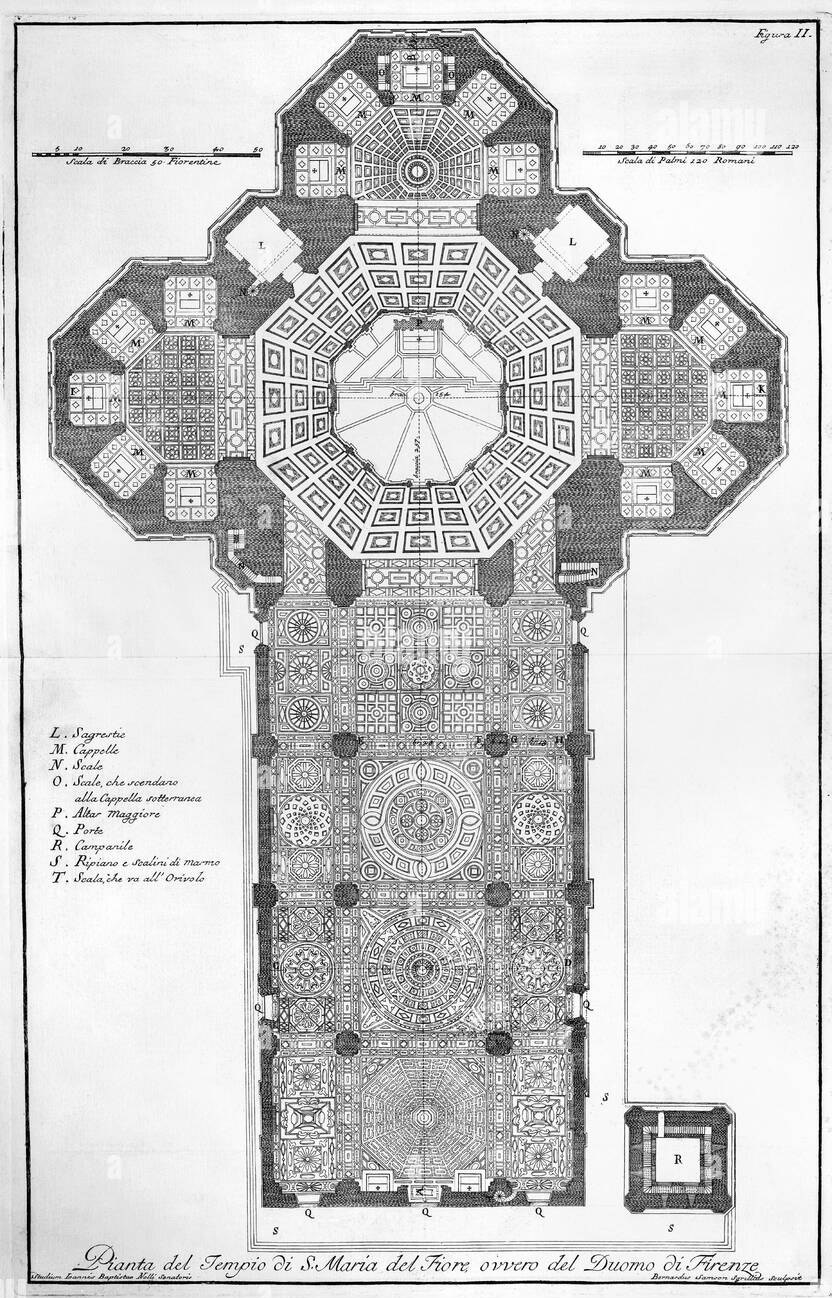

After a hundred years of construction and by the beginning of the 15th century, the structure was still missing its dome. Arnolfo di Cambio designed the essential features of the dome in 1296. His brick model, 4.6 m (15.1 ft) high, 9.2 m (30.2 ft) long, was standing in a side aisle of the unfinished building and had long been sacrosanct. It called for an octagonal dome higher and wider than any had ever been built, with no external buttresses to keep it from spreading and falling under its own weight.

The commitment to reject traditional Gothic buttresses was made when Neri di Fioravanti’s model was chosen over a competing one by Giovanni di Lapo Ghini. That architectural choice, in 1367, was one of the first events of the Italian Renaissance, marking a break with the Medieval Gothic style and a return to the classic Mediterranean dome. Italian architects regarded Gothic flying buttresses as ugly makeshifts.

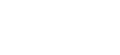

Furthermore, the use of buttresses was forbidden in Florence, as the style was favored by central Italy’s traditional enemies to the north. Neri’s model depicted a massive inner dome, open at the top to admit light, like Rome’s Pantheon, partly supported by the inner dome but enclosed in a thinner outer shell to keep out the weather. It was to stand on an unbuttressed octagonal drum. Neri’s dome would need an internal defense against spreading (hoop stress), but none had yet been designed.

The building of such a masonry dome posed many technical problems. Brunelleschi looked to the great dome of the Pantheon in Rome for solutions. The dome of the Pantheon is a single shell of concrete, the formula for which had long since been forgotten. The Pantheon had employed structural centering to support the concrete dome while it cured.

This could not be the solution in the case of a dome this size and would put the church out of use. For the height and breadth of the dome designed by Neri, starting 52 m (171 ft) above the floor and spanning 44 m (144 ft), there was not enough timber in Tuscany to build the scaffolding and forms.

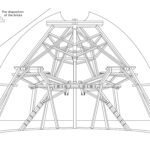

Brunelleschi chose to follow such design and employed a double shell of sandstone and marble. Brunelleschi would have to build the dome out of brick due to its lightweight compared to stone and being easier to form, and with nothing under it during construction. To illustrate his proposed structural plan, he constructed a wooden and brick model with the help of Donatello and Nanni di Banco. This model is still displayed in the Museo dell Opera del Duomo. The model served as a guide for the artisans but was intentionally incomplete to ensure Brunelleschi’s control over the construction.

Brunelleschi’s solutions were ingenious. The spreading problem was solved by four internal horizontal stone and iron chains, serving as barrel hoops, embedded within the inner dome: one at the top, one at the bottom, and the remaining two evenly spaced between them. A fifth chain, made of wood, was placed between the first and second of the stone chains. Since the dome was octagonal rather than round, a simple chain, squeezing the dome like a barrel hoop, would have put all its pressure on the eight corners of the dome. The chains needed to be rigid octagons, stiff enough to hold their shape and not to deform the dome as they had it together.

Brunelleschi’s stone chains were built like an octagonal railroad track with parallel rails, and cross ties, all made of sandstone beams 43 cm (17 in) in diameter and no more than 2.3 m (7.5 ft) long. The rails were connected end-to-end with lead-glazed iron splices. The cross ties and rails were notched together and then covered with bricks and mortar of the inner dome. The cross ties of the bottom chain can be seen protruding from the drum at the base of the dome.

The others are hidden. Each stone chain was supposed to be reinforced with a standard iron chain made of interlocking links. Still, a magnetic survey conducted in the 1970s failed to detect any evidence of iron chains, which, if they exist, are deeply embedded in the thick masonry walls. Brunelleschi also included vertical “ribs” set on the corners of the octagon, curving towards the center point. The ribs, 4 m (13 ft) deep, are supported by 16 concealed ribs radiating from the center. The ribs had slits to take beams that supported platforms, thus allowing the work to progress upward without scaffolding.

A circular masonry dome can be built without supports, called centering because each course of bricks is a horizontal arch that resists compression. In Florence, the octagonal inner dome was thick enough for an imaginary circle to be embedded at each level, a feature that would hold the dome up eventually but could not hold the bricks in place while the mortar was still wet. Brunelleschi used a herringbone brick pattern to transfer the weight of the freshly laid bricks to the nearest vertical ribs of the non-circular dome.

The outer dome was not thick enough to contain embedded horizontal circles, being only 60 cm (2 ft) wide at the base and 30 cm (1 ft) thick at the top. To create such circles, Brunelleschi thickened the outer dome at the inside of its corners at nine different elevations, creating nine masonry rings, which can be observed today from the space between the two domes. The outer dome relies entirely on its attachment to the inner dome and has no embedded chains to counteract hoop stress.

The exterior of the Cathedral

A modern understanding of physical laws and the mathematical tools for calculating stresses were centuries in the future. Like all cathedral builders, Brunelleschi had to rely on intuition and whatever he could learn from the large-scale models he built. To lift 37,000 tons of material, including over 4 million bricks, he invented hoisting machines and lewissons for hoisting large stones.

These specially designed machines and his structural innovations were Brunelleschi’s chief contribution to architecture. Although he was executing an aesthetic plan made half a century earlier, his name, rather than Neri’s, is commonly associated with the dome.

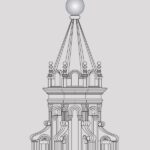

Brunelleschi’s ability to crown the dome with a lantern was questioned, and he had to undergo another competition, even though there had been evidence that Brunelleschi had been working on a design for a lantern for the upper part of the dome. The evidence is shown in the curvature, which was made steeper than the original model.

He was declared the winner over his competitors, Lorenzo Ghiberti and Antonio Ciaccheri. His design (now on display in the Museum Opera del Duomo) was for an octagonal lantern with eight radiating buttresses and eight high-arched windows. Construction of the lantern was begun a few months before his death in 1446. Then, for 15 years, little progress was possible due to alterations by several architects.

The lantern was finally completed by Brunelleschi’s friend Michelozzo in 1461. The conical roof was crowned with a gilt copper ball and cross containing holy relics by Verrocchio in 1469. This brings the total height of the dome and lantern to 114.5 m (376 ft). This copper ball was struck by lightning on 17 July 1600 and fell down. It was replaced by an even larger one two years later.

Facade of the Florence Cathedral

The original façade, designed by Arnolfo di Cambio and usually attributed to Giotto, was begun twenty years after Giotto’s death. A mid-15th-century pen-and-ink drawing of this so-called Giotto’s façade is visible in the Codex Rustici and the drawing of Bernardino Poccetti in 1587, both on display in the Museum of the Opera del Duomo. This façade was the collective work of several artists, among them Andrea Orcagna and Taddeo Gaddi.

This original façade was completed in only its lower portion and then left unfinished. It was dismantled in 1587–1588 by the Medici court architect Bernardo Buontalenti, ordered by Grand Duke Francesco I de’ Medici, as it appeared outmoded in Renaissance times. Some of the original sculptures are displayed in the Museum Opera del Duomo, behind the Cathedral. Others are now in the Berlin Museum and the Louvre.

The competition for a new façade turned into a huge corruption scandal. The wooden model for the façade of Buontalenti is on display in the Museum Opera del Duomo. A few new designs had been proposed in later years, but the models (of Giovanni Antonio Dosio, Giovanni de Medici with Alessandro Pieroni, and Giambologna) were not accepted. The façade was then left bare until the 19th century.

In 1864, a competition held to design a new façade was won by Emilio De Fabris (1808–1883) in 1871. Work began in 1876 and was completed in 1887. This neo-gothic façade in white, green, and red marble forms a harmonious entity with the Cathedral, Giotto’s bell tower, and the Baptistery, but some think it is excessively decorated.

The whole façade is dedicated to the Mother of Christ.

Curiosities of the Florence Duomo

Filippo Brunelleschi died on April 5, 1446. He was dressed in white for his funeral and placed in a casket surrounded by candles, with his eyes towards the dome he had built brick by brick. He was buried in the crypt of the Cathedral with a commemorative plaque that honors him. A great honor since, at that time, the architects were considered humble artisans and were not buried in the crypt.

One of the most remarkable features of the outside of the building is the so-called “Porta della Mandorla” (north) (Della mandorla = almond) that was given this name because of the large halo around the figure of the Virgin also sculptured by Nanni di Banco (1380/90-1421) among others.

Its interior preserves significant works of art: on the left side, we find the first two detached frescoes showing the”Condottiero Giovanni Acut” and”Niccolò da Tolentin” painted by Paolo Uccello in 1436 and by Andrea del Castagno in 1456. Paolo Uccello also frescoed the clock on the inside wall, showing four vigorous” heads of the saint.”

The many sculptures explicitly made for the Cathedral (many of which have now been moved to the”Museo dell Opera del Duomo”) also comprise the”Lunette” by Luca Della Robbia above the doors of the Mass Sacristies. The large” Piet” by Michelangelo (c. 1553) has instead been removed and transferred to the”Museo dell Opera del Duomo.”

Most of the splendid stained glass windows were made between 1434 and 1455 to the designs of famous artists like Donatello, Andrea del Castagno, and Paolo Uccello. Brunelleschi and other artists designed the wooden inlays on the sacristy’s cupboards, including Antonio del Pollaiolo.

The internal walls of the dome, which have recently been restored, were frescoed between 1572 and 1579 by Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) and Federico Zuccari (c. 1990-1609), who represented a large scene of the”Final Judgment.”

The bell tower by Giotto remains, together with the huge dome, one of the most striking views of the town. The famous painter, Giotto, was also the architect of the project for the bell tower, although, by the time of his death (1337), only the lower part had been completed. The works continued under the direction of Andrea Pisano (c. 1290-1349) and Francesco Talenti (not. 1325-1369) who completed the project.

Florence Cathedral Plans

Video: How Filippo Brunelleschi Built the world’s Biggest Dome

© National Geographic

Florence Cathedral Image Gallery

About Filippo Brunelleschi

Filippo Brunelleschi, also known as Pippo (1377 – 15 April 1446), is considered a founding father of Renaissance architecture. He was an Italian architect, designer, and sculptor and is now recognized to be the first modern engineer, planner, and sole construction supervisor. In 1421, Brunelleschi became the first person to receive a patent in the Western world.

He is most famous for designing the dome of the Florence Cathedral, a feat of engineering that had not been accomplished since antiquity, as well as the development of the mathematical technique of linear perspective in art, which governed pictorial depictions of space until the late 19th century and influenced the rise of modern science. His accomplishments also include other architectural works, sculpture, mathematics, engineering, and ship design. His principal surviving works can be found in Florence, Italy.